The Smackdown

Because the Beatles not only spearheaded their culture but also lived with the creative and political expectations of their times, the energy drain from Beatlemania was significant. By the time these two films were made in the late 1960s, the cracks were already showing — in society, sure, but also in the band which, more than ever, was beginning to look less like the Beatles and more like four guys named John, Paul, George and Ringo.

In the movie world, the Beatles had had a mixed run. Certainly A Hard Day’s Night (1964) and Help! (1965) were commercial and artistic successes for United Artists (see Smackdown). But following them up with the barely conceived Magical Mystery Tour (1967) and an arm’s length involvement with Yellow Submarine (1968) hardly signaled that the Beatles had gone Hollywood.

All the Beatles toyed with Hollywood as solo artists both behind-the-scenes and in front-of-the-camera. The first to show individual interest, though, were John Lennon in How I Won the War (1967) and Ringo Starr in The Magic Christian (1969). They each acted in an establishment-tweaking, sarcasm-bubbling and sometimes cringe-inducing films that are certainly cultural artifacts.

Want to know which one of those films works so much better than the other? As Paul McCartney wrote in a song that went into his buddy Ringo’s film, “Come and Get It.”

![How-I-won-the-war]() How I Won the War (1967)

How I Won the War (1967)

United Artists hired Richard Lester, the director of the first two Beatles films, to create an anti-war spoof based on Patrick Ryan’s novel, How I Won the War. Lester re-applied his eclectic film technique (non-linear narrative, rat-a-tat editing, smart dialogue), and more importantly, was able to cast John Lennon in a smallish role as a mumbling musketeer.

It’s a mystery how any country could win World War II with anyone as inept and naïve as Lt. Earnest Goodbody (Michael Crawford) leading troops. The story plays as a sort of faux-memoir, with Goodbody flailing about, trying to bring discipline to the sort of misfits you’d find in Hogan’s Heroes or F-Troop, only not as funny.

Within the group, musketeer Gripweed (Lennon, serving up the first view of his signature round eyeglasses), is as mouthy and casually committed as the rest. The troops show no interest in following orders to build a cricket field behind enemy lines in North Africa, and in fact, openly discuss shooting Goodbody instead. Crawford , who later distinguished himself in Phantom of the Opera, has his character slip into the sort of reveries that may have informed Mike Nichols’ direction of 1970’s Catch-22, but Goodbody never reaches Yossarian’s heights or depth.

Somehow, Goodbody survives the war, although Gripweed and most of the group do not. Along the way we come to understand his men’s revulsion for him, as Goodbody is revealed to be as much a fascist and anti-Semite as the people he’s fighting. Screenwriter Charles Wood cobbled the story together from a novel by Patrick Ryan and Wood’s own play, Dingo.

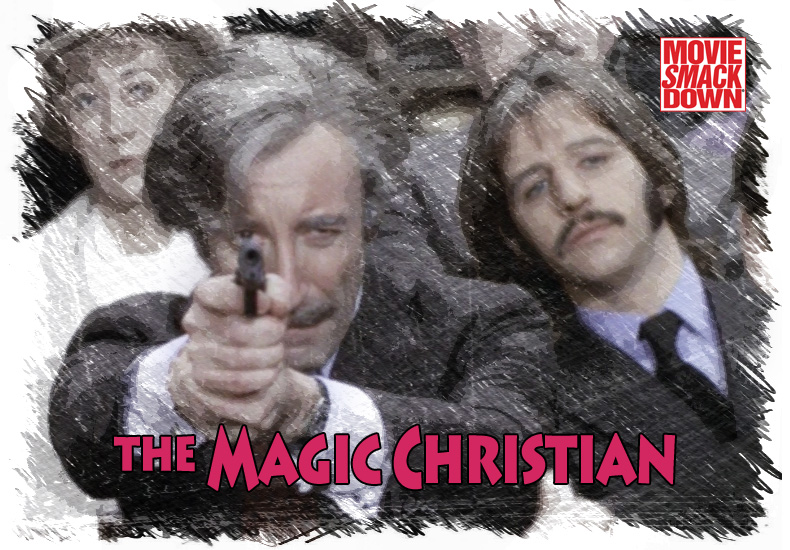

The Magic Christian (1969)

The cast-a-Beatle-in-an-offbeat-morality-tale formula continued with the 1969 black comedy, The Magic Christian. Here, The Goon Show’s Joseph McGrath directed some of his well-known TV pals plus Ringo Starr, from a script McGrath wrote with Terry Southern from Southern’s book. This film is conventional in structure, but something else entirely in execution. Modern civilization takes it right on the chin, over and over.

Everything is possible for Sir Guy Grand (Peter Sellers, in prime form), and why not? He has boundless cynicism and enough money to bankroll every whim. He adopts a homeless derelict (Ringo Starr), and together they set out to prove Sir Guy’s motivating premise — that everyone has his price and is often willing to debase himself in unspeakable ways to get it.

Two boxers turn a heavyweight fight into a romantic interlude. Laurence Harvey turns Hamlet’s soliloquy into a cheeky striptease. The incidents continue to escalate in both stakes and outrageousness as, again and again, thanks to Grand’s generous cash offers, people trade their better sense for a payoff.

The final stunt has Sellers and Ringo enticing dozens of brave extras to pursue thousands of bank notes, which the wealthy Sir Guy has had dumped into a giant vat of urine, blood and animal entrails from a slaughterhouse. It’s a classic bit that flirted with film immortality when the National Parks Service amazingly agreed to provide the grounds of the Statue of Liberty for that splash-for-cash location. The studio ultimately refused to pay for the shoot, though, so the scene was filmed on an empty lot in London. Had it been shot as envisioned, it’s hard to imagine talking about anything else in the movie.

The Scorecard

If you think the Beatles are hot now, you should’ve been around in the mid-’60s, when Beatlemania took hold. The lads from Liverpool had a minor hit in England with “Love Me Do” in late 1962, but it’s safe to say most Americans had heard little of them before their February, 1964 appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, at which point, without the help of 24-hour cable or TMZ or Tina Brown, it was suddenly all Beatles, all the time. A couple of months later, on April 4, they held all top five slots on the record charts, and by the next week had charted an additional two songs, giving them an unheard of fourteen hits out of Billboard’s Hot 100.

All of this is by way of saying that there is a tremendous pool of support for all products made by the Beatles as a group or as solo acts. Nostalgia, talent and the promise of fun have always made any Beatles project worth paying attention to.

Even so, How I Won the War confused me as a teenager and still does 45 years later. I’m not the first person who got lost in the various English dialects, including that of John Lennon, who carries co-star billing but is barely in the movie and seems to swallow what dialogue he has. Maybe my own tin ear is to blame, but the film’s real problems remain structural, not linguistic. During his salad days, Lester created magic onscreen with a visual style that featured characters speaking directly to the camera; clipped, jerky dialogue; and editing tricks that throw time and space out of sequence. It works marvelously in Help! but here, not so much.

The humor seems labored, and so is the bellyaching by the musketeers – I was rooting for them to just shoot Goodbody and get it over with. And Goodbody is not the only annoying character. Jack MacGowran’s loony Juniper offers nonstop commentary like a court jester in khaki. Unfortunately, little of it is funny.

The Beatle factor is put to better use in The Magic Christian. Ringo is onscreen quite a bit, though there’s so much going on that, charming as he is, he gets lost in the mayhem. Truth be told, neither Lennon nor Starr does much acting in these films. In Christian, Peter Sellers takes over, playing Guy Grand with obvious glee. In his capable hands, the material delivers body blows to capitalism, hypocrisy and intolerance with relentless gusto.

The rest of the cast is also consistently more interesting than the mostly unknown actors in War. Richard Attenborough, Laurence Harvey, Raquel Welch, Christopher Lee, Roman Polanski and Yul Brynner (memorable as a transvestite torch singer) all make notable cameos, relishing their short time onscreen, even if the critics had reservations.

Both films have similar plusses. How I Won the War develops atmosphere through the effective use of recorded wartime songs and evocative music composed and conducted by Ken Thorne. Another highlight is David Watkins’ cinematography. The Magic Christian features fine camerawork, as well, from Geoffrey Unsworth (2001: A Space Odyssey), and a bouncy, semi-classic theme song, “Come and Get It,” written by another Beatle, Paul McCartney, for the group, Badfinger.

The Decision

It’s clear John Lennon and Ringo Starr were grafted onto these movies. Ringo’s character does not exist in Terry Southern’s novel. Lennon’s is frankly not that memorable. John is better known for writing “Strawberry Fields” during the location shoot for this film in Spain. As mementoes of Beatlemania, both films have value, but their quality as movies is another matter. How I Won the War is an exasperating mishmash of narrative styles, dull parody, forced symbolism (such as the use of life-size toy soldiers), and unsympathetic characters. The Magic Christian better celebrates its excesses, and its targets are more sharply defined. It also has that necessary ingredient for black comedy: It’s funny. For that reason alone, it’s easy to forgive our winner, The Magic Christian, for being way over top. McCartney’s hit pop tune is just gravy.